The death of writing, gradually then suddenly: new post on Substack

https://frederickguy.substack.com/p/watching-as-reading-and-writing-become

The death of writing, gradually then suddenly: new post on Substack

https://frederickguy.substack.com/p/watching-as-reading-and-writing-become

New blog posts will appear on Substack:

As a business deal, Trump’s tariffs seem to make sense for Trump and Trump only: Trump, the shake-down artist. As many have pointed out, what the President gets out of this is a queue of CEOs begging him for exemptions; in return all he’ll ask is loyalty, public admiration and some display of … generosity. As economic policy for the country of which Trump happens to be president it is of course crazy – the tariffs are Smoot-Hawley Mark II, with some amplifying factors: economic activity in today’s world crosses borders a lot more than it did in 1930; nations are more specialized and thus dependent on exports and imports; production processes skip back and forth across borders, so that trade barriers will affect almost every manufactured product, even if made for domestic consumption; also, Trump’s mafia-boss shakedown mode, himself imposing and revoking tariffs personally as President, adds greatly to economic uncertainty, which will further undermine both capital investment and the purchase of consumer durables. So it’s mad, economically, we know that. That’s how mafias work, and how mafia states work: most people are losers, but the boss does well.

Trump’s tariffs and digital platforms

Still, Trump does have some constituents whose welfare he is concerned with. At this point his circle of concern may be small, but it does seem to include the oligarchs who back him, in particular those controlling big digital platforms: they are, now, his political base, those who stood closest to him, wives at their sides, while he was sworn into office. Are their interests threatened by a trade war? Spencer Hakimian hints at this risk in a post on ex-Twitter (sadly he doesn’t seem to be on Bluesky yet):

I reproduce this post because it offers a simple picture of America’s trading relationship with Europe, and for that matter with the rest of the world: the US exports less in the way of material things, more in the way of intangibles. A lot of the intangibles – what Hakimian calls “tech software and financial services” – are things controlled by big digital platforms, delivered over the Web: social media; internet search; the two smartphone platforms; the three major payment platforms (Visa, Mastercard and Paypal are behind Apple/Amazon/Google/Microsoft/Meta in market capitalization, but are still among the world’s most valuable companies); the biggest TV/movie/general video streaming platforms; the great suppliers of general purpose software (Microsoft, Adobe, Oracle…); Amazon’s everything store.

So is Trump, with his rash tariffs, endangering the lucrative platform business? At first look it appears not, but Europe could make it so.

It first appears not, because most of the platforms’ revenue isn’t from trade – it’s simply repatriated profits from overseas subsidiaries which export almost nothing from the United States; in other cases it is trade in digital services and as such exempt from tariffs under a WTO moratorium that’s been in place since 1998. Raising tariffs doesn’t hurt Amazon, or Visa, or Netflix.

The tariff exemption for streamed services may not last, though: large developing countries such as India and Indonesia have long opposed it, and will push again to end it in 2026. But the far bigger, and tougher, issue is the power of platforms when they aren’t selling anything across borders – they might sell advertising for their global platform locally in each country, or license rights to subsidiaries located there; indeed, much of what is now streamed internationally could probably also be handled that way, if the exemption which now protects them is lost, and could thus remain tariff-free. In this light Trump’s tariff tantrum might make some kind of avaricious sense – the US can put steep levies on imports of manufactured products and raw materials, while American digital platforms would continue to rake in revenues from around the world, tariff-free.

All countries will, of course, put up retaliatory tariffs on goods. This is necessary but just creates an unpleasant standoff in those markets where tariffs apply, while America’s platform oligarchs thrive unmolested.

Hit him where it hurts: Europe can take the fight to the platforms

Europe is in a position to do something about the power of the platforms: this would be good for European consumers and businesses, and bad for Trump. Which is to say, win-win.

The global dominance and immense profitability of the American platforms has been possible not just because those firms moved first to use web technologies, but also because governments have allowed it. To date, the only serious challenge has come from China, which has shut out many of the American platforms and fostered its own domestic Web giants, such as Tencent and Alibaba. Mario Draghi, in his influential report to the European Commission, advocates the creation of European mega-platform companies. Draghi writes in connection with concerns about European labor productivity – the value of output per hour of labor – which has not kept up with that in the US. He notes that the growth of America’s productivity advantage is due to “tech”. This is true and yet it also shows why productivity is, in this case, a very bad guide to policy: a highly profitable monopoly of course has high labor productivity, because the monopoly profits are part of value added – if you divide Microsoft’s profit by its number of employees, each of them looks quite productive. Europe’s economy lacks such big monopolies and is thus more competitive, which is a good thing for all but any would-be European oligarchs.

Moreover, even if Europe wanted them, it’s not clear it could create mega-platforms. The existing platforms benefit, in their nature, from huge scale economies. Replicating them would be impossible in head-to-head competition; China avoided head-to-head competition by simply shutting out the American platforms, but the China strategy is incompatible with an open society, and would also be economically destructive if replicated in Europe. (Europe could get serious about expanding its digital technology sectors, with an initiative such as Eurostack, but that does not require a monopolistic platform.)

What Europe can do instead is to get serious about instilling openness and competition in the markets now dominated by platforms. Platforms are network services – that is what gives them their scale economies and their power. A century and more ago, earlier generations of network services – railroads, electric power, landline telephones, and so on – were brought under either public ownership or strict regulation everywhere in the world, by governments of both right and left, both in countries with market economies and in those styled communist. The reason governments everywhere made that choice, independently of each other and for numerous different networks, is that these networks were essential for the modern economy, and no government could afford to let an economically essential network be held ransom by some robber baron.

The same goes for web services today. Why should you need to use Microsoft’s or Adobe’s proprietary product to make the files you create reliably readable by others? Why should you need to subscribe to multiple streaming services in order to have access to the occasional movie or sporting event of your choice? Why should the major online public marketplace, connecting buyers and sellers, be operated by a single extremely profitable company? Because our governments have allowed it, that is the beginning and end of the story.

What the platform oligarchs fear most is this: that parts of their platforms will be subjected to market competition, and other parts where competition is not feasible will become public utilities operating on the common carrier principal. To avoid that outcome, the oligarchs – most of them former liberals – are apparently happy to live in a fascist state. The reason they pivoted so decisively behind Trump in last year’s election is that the Biden administration had finally reversed America’s nearly fifty year retreat from anti-trust enforcement: an astonishing team including Lina Khan chairing the Federal Trade Commission, Jonathan Kanter heading the Justice Department’s Anti-Trust Division, Rohit Chopra heading the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and Tim Wu as Special Assistant to the President for Technology and Competition Policy, were at work battling the platforms in the American courts. So the oligarchs backed Trump, and won.

But won only in America. And now Trump is trying to bully the rest of the world on trade (and possibly on supporting the dollar), with the platform oligarchs at his back. Europe is a very large market, and the European Commission has responsibility for market competition throughout the EU. Anything Europe does to bring the platforms to heel can be – and will be – copied by other governments around the world: this is where Trump and his oligarchs can be beaten. The Commission does have ongoing efforts to bring the platforms into competitive markets – enough to make both Trump and the platform oligarchs upset, but far too slow, and on too many occasions too soft. Now that Trump has decided that Europe is his enemy, and has launched his crazy tariffs on the world, it is time for Europe to hit Trump, and his oligarchs, where it hurts.

Two principles animate George Monbiot’s Regenesis: environmental sustainability, and feeding people. Sustainability here is not reduced to global heating, and indeed focusses more on biodiversity. Sustainability leads him first to the soil, which is spectacular in terms of unseen biodiversity. It leads him then to the land, because in his view most agricultural and pastoral land use is inimical to biodiversity; we farm ever more land – he calls it “agricultural sprawl”.

Adding to the sustainability problem the need to feed people, and feed them well, gives Monbiot a circle to square: how to reconcile biodiversity with the food supply. Not eating animal products is his first step, a venerable bit of advice. Having myself arrived at a venerable age I can say that I first saw it in Frances Moore Lappe’s Diet for a Small Planet (1971), a bad cookbook but an eloquent primer on non-meat protein. It grows from the simple arithmetic of the amount of land required to feed us indirectly (intermediated by cow) vs. directly. And, in addition to fostering biodiversity by using less land, cutting out lmeat does wonders in various ways for reduced greenhouse gases, water supply and quality, and so forth. But, says Monbiot, eliminating animal products is still not enough. What he proposes would shake up an order we’ve had since the Neolithic revolution, over 10,000 years ago.

I’ll come to the solutions he offers but I need first to say that I read Regenesis a few months ago, and have been moved to write this now by reading a really disappointing review it by Tim Flannery in The New York Review of Books. Flannery’s one of their regular writers, and sometimes their regulars seem able to submit some pretty thin stuff, at least by the usual high standard of the New York Review. Most surprising to me is that Flannery, a veteran and well-regarded writer on environmental questions, all but ignores Monbiot’s core claim about agriculture and biodiversity, and will brush aside carefully argued and documented arguments with no argument or evidence of his own. He sort of grumbles his way through the review. So, I’ll grumble back.

Monbiot is critical of many fashionable solutions to the problems he poses. His take on localism and on global food markets is (appropriately) complex, and I’ll save that for another time. His gentle takedown of Michael Pollan (“a man for whom I have great respect, though I find his rule hard to comprehend: ‘Don’t eat anything your great-great-grandmother wouldn’t recognize as food’ “) leads us to meet Monbiot’s late grandmother and what she would have recognized as food which, for all his fond memories of fishing and foraging with her, is a list that does not include most of what Monbiot now eats or considers healthy. Similarly, he likes urban gardens on mental health grounds but dismisses their importance for feeding the world with a simple calculation of the amount of farmable surface they – whether traditional allotments or high-tech vertical farms – can provide. Flannery grumbles that mental health doesn’t provide much motivation for urban farming but doesn’t dispute – or for that matter, explain – Monbiot’s claims.

More consequential is Monbiot’s argument about grazing. When he says “agricultural sprawl”, you can take that as a signal that he sees extensive as a bigger problem than intensive agriculture.

We know that conventional livestock farming is unsustainable because its land footprint goes so far beyond that of the feedlot for cattle: deforestation today is proceeding largely to make room for agriculture, and most of that to grow fodder, as the number of farm animals on Earth explodes. Monbiot goes on to claim that grass fed beef is even worse in this regard than beef fattened in feedlots, because it requires more land; organic beef is, he says, worst of all, taking still more land because it grows more slowly and so occupies the land for longer before it reaches your table.

The point Monbiot is making here can be made into a two-part question. The first part is whether, on particular pieces of land, raising livestock does more, or less, damage via lost biodiversity and net contribution to greenhouse gases, than some other source of food would cause. Call that the “is this particular hamburger sustainable?” question, or the one cow at a time question. I’d like to think the answer is “yes”, if only because one of my sisters raises grass fed beef and we all like the product. Sadly, Monbiot says that the answer is generally “no”. I won’t go into the details – you can read the book, and it is pretty detailed. His assessment of Allan Savory’s Ted-Talk-famed rotational grazing system (“I like Allan. When I was diagnosed with cancer, he sent me a kind and charming email. I know he’s sincere and believes what he says. But…”) is a polite four-page takedown, tightly argued and thoroughly sourced. And so on with other aspects of the problem. Perhaps Monbiot once wrote “I like Tim, nice guy, love his work, but…”; it could explain Flannery’s review.

The second part of the question is: if some hamburgers can be obtained in a sustainable way – a big if from a climate standpoint because of the methane from cattle, but plausible at least in terms of biodiversity – how many people could be fed by them? His answer: not many, because it takes so much land; it would be a luxury product for a few, it’s not a serious way to feed the world. He arrives at this conclusion by extrapolation from a single well-known farm where the cattle and pigs frolic with wild animals; however, if he is correct about Savory and related points, the data is not much of a problem because this second question then answers itself. It is worth asking as a distinct question only because some people will frame the problem as a personal choice about consumption, and some will frame it as a collective choice about the nature of our food supply system.

Others will dispute Monbiot’s conclusions, going back to methods like Savory’s and claiming (as Flannery does) that “methods such as rotational grazing have led to impressive soil and biodiversity restoration.” Now, the New York Review is rare in that it will allow its reviewers to cite the occasional source, complete with footnote; confronted as he is with Monbiot’s considerable bibliography, Flannery might have taken the occasion to provide a source for his assertion, but he doesn’t, falling back instead on his authority as an Australian who knows a thing or two about grazing that an Englishman does not.

Much of Monbiot’s book takes the form of exploring different solutions to the sustainability/food supply conundrum. The book is organized around cases, practical efforts being implemented by particular people, most of whom Monbiot visits. Monbiot is always in the story, and he usually makes that story interesting. In this book, he has his presence a little more under control than he had in Feral (2013), his book about rewilding. Parts of Feral seem to have been written by a George Monbiot wilderness action hero – perhaps the whole point is that he’s a feral narrator – which wasn’t bad storytelling but clashed a bit with the social and scientific arguments he was trying to get across. In Regenesis the character he projects is more a person trying very hard to find solutions to this tough problem, and talking with a lot of interesting people about it. He makes films on the topic as well, and that shows in the style.

Feral is, though, good background reading for Regenesis, because it gives you a picture of what Monbiot would do with all that land he doesn’t want to have in agriculture. You will come then to picture, when he talks about agricultural sprawl, those large parts of Ireland and the western side of Great Britain where temperate rainforest once stood, and are now devoted to grazing sheep or cattle, becoming forest again.

Of the several cases Monbiot considers in Regenesis, three stand out because he seems to think they represent models that work, or will work. These three could be seen as his proposal, his three-legged stool to support a sustainable food supply. One of these is a vegetable farm in England, run by a man named Tolly; second is a facility producing proteins in a hydrogen-driven fermentation process in a vat in Finland; third are perennial varieties of rice and wheat (those we’ve eaten heretofore, which is to say since the Neolithic, are all annuals), grasses which set down deep roots and have friendlier relationships with soil, water, pests and variable weather.

I won’t try to relate the details of any of these. Tolly is doing intensive agriculture, mixed crops closs together, working with flowers and insects, doing some kinds of alchemy with the soil. He seems to be emerging from a long tradition, but experimenting relentlessly, studying the science, and adjusting the practice. He also teaches it. A nice story, and I’m sure more to tell a gardener or farmer than it tells me.

The attractiveness of Tolly’s farm is that it produces high yields (per area) without pesticides or chemical (or even animal) fertilizer, and enhances biodiversity both above and below ground, all starting with some low-quality, stony soil. Monbiot makes clear that Tolly’s farm requires a lot of labor and, while it grows and sells a lot of good food, it hardly makes any money. Flannery picks up this point, and it’s important that we understand what its implications are: it means that Tolly’s practices, as they stand, have lower labor productivity than conventional farming practices. That means that, if all our vegetables were grown as Tolly grows them, they would be more expensive; to put it another way, to feed the world with these methods would require shifting some of the workforce back into agriculture (or at least, the vegetable-growing part of agriculture), reversing a centuries-long trend. But the picture isn’t that bad if we take Monbiot’s ambition as a whole, which would substantially reduce the overall amount of agriculture, so we’d have more labor devoted to vegetables and less to other food.

But I’m getting ahead of my story. Back to Tolly’s farm: its present unprofitability does not mean that Tolly’s approach cannot become viable as a business model. If the world’s farmers were restricted to growing vegetables in a sustainable way, what is now conventional would be history, and Tolly’s model could be quite profitable. In this it is like many sustainable methods which look too expensive: internalize – or prohibit – the externality, and options suddenly look different.

The other thing striking about Tolly’s approach is that it seems to require not only a lot of work, but a lot of knowledge, and ongoing experimentation and adjustment. Some of that, of course, will be because he’s doing something unusual, and if it were to become a standard approach to farming some of the knowledge would become standardized. Even so, it does seem to rely on the ongoing application of science to particular local conditions and events; I would be surprised if, even as a standard practice, it did not require a higher level of education, and ongoing learning and decision making, than other ways of growing vegetables do. File that thought away for some future discussion of education for sustainability.

Growing protein in fermentation vats is something you’ve probably seen in the news. The science advances, they’re working on fats and the texture of “meat”, and so on. The process requires a hydrogen input, so is zero carbon only if there’s zero carbon electricity to produce the hydrogen, but that’s becoming cheap. Monbiot’s dream is local solar-powered “breweries” throughout the world; his nightmare is that corporations will have control over key patents and effectively tax this vital new global food supply. Flannery’s nightmare is that such a system puts all our eggs in one basket, vulnerable to whatever future pathogen finds its home in the fermentation tanks. Both nightmares strike me as sensible ones. As for the adoption of the technology itself, and its displacement of meat production, Monbiot is optimistic. As the cost of the fermented product comes down, he reasons, a tipping point will come, where the fermented product quickly replaces the cheaper cuts of real meat – what goes into ground beef and sausage and chicken nuggets and cat food. This will make the more expensive cuts (which can’t yet be replicated in the fermented versions) more expensive still, reducing the market for them. Meat, thus, would rapidly be replaced. Here’s hoping. It should be noted that this tipping point would be brought forward in the schedule by any policies which raise the price of real meat, for instance through restrictions on the environmental damage done by meat production, or the reduction of subsidies to its production; internalization of externalities, again.

Most exciting (to me, because it was new to me) is the third leg of Monbiot’s stool, perennial grain. Perennial rice has become a thing in China, its spread limited by the seed supply, and particularly popular where erosion is a threat (the roots grow deep, the soil remains covered year round). Wheat seems to be on the way.

Tolly’s methods and perennial grain both, for Monbiot, show the possibilities for an agriculture which is friendlier to biodiversity, both below and above ground. Both would represent big changes. But those changes look small when compared with the move away from animal products, to proteins from vegetables or from fermentation. Such a move would make possible a wholesale shift of land from agriculture to wilderness. Fermentation is so attractive to Monbiot not because it can replicate meat, but because it would free us from the rivalry between food supply and wilderness.

The new wilderness would have some benefit in terms of carbon sequestration, and a huge benefit in terms of biodiversity. Exactly how much of the planet needs to go back to wilderness to prevent the collapse of biodiversity is not something we can know; in Half-Earth (2016), Edward O Wilson said 50%, and the satisfying roundness of the figure tells you just how uncertain it is. But the problem is a serious one, less well quantified than climate change but similarly threatening. See Wilson’s The Diversity of Life (1992) for the biology, or Partha Dasgupta’s Economics of Biodiversity (2021) for … the economics. From either perspective, one of the requisites is setting a lot of land and sea aside. Monbiot’s project is showing how we could do that while still feeding everybody.

I could go on – there’s a lot in this book. The chapter dealing with a food bank is quite good, as is the material on localism and on the inter-connected global food system. I can’t say that Flannery dismisses what Monbiot is saying, it’s more that he ignores most of what the book does, and grumbles about what he doesn’t ignore. It is always tempting to criticise Monbiot, because he’s an enthusiast, he looks for solutions and gets excited about them. But he does put in the work, both to understand the complex and pressing problems we face, and to assess the possibilities and limitations of the different solutions he explores. This is an important book, and if you’re going to grumble about it you should show your receipts.

References

Dasgupta, Partha. 2021. “The Economics of Biodiverity: The Dasgupta Review | Royal Society.” February 2. https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/projects/biodiversity/economics-biodiversity/

Flannery, Tim. 2022. “It’s Not Easy Being Green”. The New York Review of Books. September 22.

Lappé, Frances Moore. 1971. Diet for a Small Planet. New York: Ballantine Books.

Monbiot, George. 2013. Feral. Allen Lane.

———. 2022. Regenesis. Allen Lane.

Wilson, Edward O. 1992. The Diversity of Life. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

———. 2016. Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. WW Norton & Company.

Russia is at odds with the rest of Europe because its dependence on the sale of fossil fuels has made it a classic petro-tryanny, incompatible with European institutions and afraid of the example they set. The Russian autocracy’s power will fade as we wean ourselves from fossil fuels.

There’s a lot said now about 15–minute cities, 20–minute neighborhoods, active travel, walkable towns: re-making the places we live so that our daily needs are within easy reach by foot or by bike. Renewing cities in this way has considerable benefits for environmental sustainability, health, and social life. One fly in the ointment is this: switching from a car-dominated city to a 15-minute one could turn into a recipe for high food prices, poor quality and reduced variety. The best tool we have to prevent this is the public market – public facilities with multiple private stalls – for fresh food. To get such markets, well run and on sufficient scale, will require sustained efforts by municipal authorities.

Like many, I have written about how such markets can help revive town centers. Public markets are also a good example of what Eric Klinenberg (2018) calls “social infrastructure” – the routine meeting places in which valuable social bonds are established and renewed. What I’m saying here is that we need them for an additional reason: to maintain competition in the retail provision of daily necessities generally, and fresh food in particular.

When you think about sustainability or about community, planning for competitive markets may not be on your list of requisites. City planners tend not to think much about it either: the shopping districts in my borough in of London are ranked by planners in terms of whether they have a large supermarket, not whether they offer a choice of them; similarly, material on 15-minute cities and 20-minute neighborhoods tends to speak in terms of “availability” of retail services – small shops and, in some versions, supermarkets – within the relevant radius.

For most of us, the facility supplying food and other daily household necessities is a large supermarket. A single large supermarket serves a substantial population, and for that reason most households cannot have several supermarkets within a 15-minute active travel ambit. When large supermarkets are in competition with one another, it is because many of their customers drive to buy their groceries, and can choose which supermarket to drive to. That means that I, as a walk-in customer to my local supermarket, am in fact depending on others who drive there, however much I resent their fumes. If the same supermarket were serving only those of us who arrived on foot, we would be a captive market and would pay for that in higher prices, reduced quality, reduced selection, or some combination of those: that is simply how monopolies behave.

That is why the venerable institution of the public market offers a simple way to get the benefits of competition in food retailing within a sustainable fifteen-minute neighborhood. With a large number of stalls for small traders, a facility on the same scale as a supermarket can provide internal competition in the supply of fresh foods – vegetables, fruits, meat, fish, baked goods, dairy, and prepared food to take away. That is not of course everything you find in a supermarket; many of the branded, packaged products you find there are better handled by conventional retailers, either shops or on-line. But fresh foods – perishables – are things many households buy one or more times each week; unlike branded, non-perishable goods, with fresh foods you depend for quality on the particular retailer you buy from, which makes it more important to have a choice of retailers. It would be a serious flaw in a fifteen-minute city not to have good competitive supply of these things within that 15-minute radius.

You might ask why a public market, with its relatively small stalls, is important for this purpose; would not small, separate shops do the job as well? Yes, small shops could, up to a point. I wrote a paper (Guy, 2013) showing that competition from car-oriented supermarkets can actually raise prices (and reduce product variety) in small shops that depend on walking trade; if the policies promoting the 15-minute city do enough to discourage driving, then in many cases small shops could step into the gap and improve their offer as they compete for the enlarged local trade. In many cases, however, there will not be enough small shops within that 15-minute radius to create the competitive market we need; moreover, a neighborhood could equally well up dominated by a single (walkable) supermarket. By providing space for small-scale (smaller than most small shops) vendors, a public market can ensure that competitive supply of fresh foods continues, even in the a car-free 15-minute neighbourhood.

Public markets have been with us for time immemorial. Many cities still have them. Everywhere, though, they have been undermined, and in many places they have been destroyed, by the car-subsidized supermarket model and by failure of cities to understand the market’s vital role. We should embrace such markets, not simply as a nice feature for a city or town to have, but as a practical necessity for making a transition to active travel.

References cited above:

Guy, F. (2013) ‘Small, Local and Cheap? Walkable and Car-Oriented Retail in Competition’, Spatial Economic Analysis, 8, 425–442.

Klinenberg, E. (2018) Palaces for People: How to Build a More Equal and United Society, New York.

Some useful sources on public food markets:

Municipal Institute of Barcelona Markets Website (English version) of the governing board for Barcelona’s municipal markets. Shows a bit how it’s done.

Urbact Markets: markets are the heart, soul and motor of cities. This is the report (2015) of the Urbact Markets European project to promote urban markets, in which several cities and regions took part: Attica (Greece), Dublin (Ireland), Westminster (United Kingdom), Turin (Italy), Suceava (Romania), Toulouse (France), Wrocław (Poland), Pécs (Hungary) and Barcelona.

Understanding London’s Markets. Mayor of London (2017)

Saving our city centres, one local market at a time. Julian Dobson, The Guardian (2015) This is an excerpt from his book How to Save Our Town Centres.

Gonzalez, S., and G. Dawson. 2015. “Traditional Markets under Threat: Why It?S Happening and What Traders and Customers Can Do.” http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/102291/.

Last month, the Haringey Council was presented with a plan for School Streets. This is where streets adjacent to schools which are closed to motor traffic in the periods just before and after school opening and closing. This has several benefits: it makes the street just outside the school safe for kids coming and going; by encouraging parents to ditch the school run and have their kids walk or cycle to school, it reduces air pollution and motor traffic, which has benefits far beyond the school in question, since the school run is a major source of road traffic.

It may be helpful here to explain the difference between school streets and low-traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs). The latter are created by simply cutting off through traffic by motor vehicles: modal filters allow people on foot or on bikes (and, if enforced by camera, buses) to pass, but stop most motor vehicles. Low traffic neighbourhoods usually don’t prohibit driving on any of the existing roads, and allow vehicle access to all addresses – it’s just through traffic that’s cut. But LTNs are in effect 24/7.

School streets are both more restrictive, and more limited. They are more restrictive because they do actually prohibit driving on certain parts of certain streets; more limited because they operate only an hour or two each day, and only on days when school is in session. And school streets stop a different kind of traffic. LTNs may reduce the school run somewhat by providing safer places for kids to walk or cycle to schol, but they don’t prevent any particular parent from driving up to the school gate to drop a kid off.

Haringey, until recently, had almost no school streets, putting it in the cellar in a recent ranking of London boroughs (Haringey has had this problem not just with school streets but with active travel – walking and cycling – generally, something I discussed last week in this blog); a few weeks ago it put in one very small one at Chestnuts Primary School. It had received some funding for school streets in London’s COVID emergency funding for active travel, but used this money mostly for footway widening without restrictions on driving – not what would usually be called school streets.

Now, though, we have a real, substantial plan for school streets, with a ranking of projects by the school’s need and the practicality of implementation. An excruciatingly slow rollout (three schools per year, primary schools only) is planned, but with the plans in hand that could be accelerated as opportunities arise. Overall, this is a terrific development, a big step forward by the Haringey Council. I need to say that very clearly because what follows deals with some of the limitations of Haringey’s school street plan.

The plan rates each primary school in Haringey as either suitable or not suitable for a school street; if suitable, some specific measures are proposed. In most cases, the key (and most expensive) measure is the installation of automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) cameras to enforce restrictions on driving.

Here, then, are the limitations of plan as I see them.

Can’t have a school street here – we need it as a rat run

Consider Devonshire Hill Nursery and Primary School, on Weir Hall Road, N17. The Plan says:

The school is not suitable for a school street despite the ‘medium’ air quality and high car usage. Weir Hall Road is not suitable for a school street as the restriction of this street would have significant impact on the operation of the road and surrounding road network as it is the main alternative connection between White Hart Lane and Wilbury Way instead of the A10.

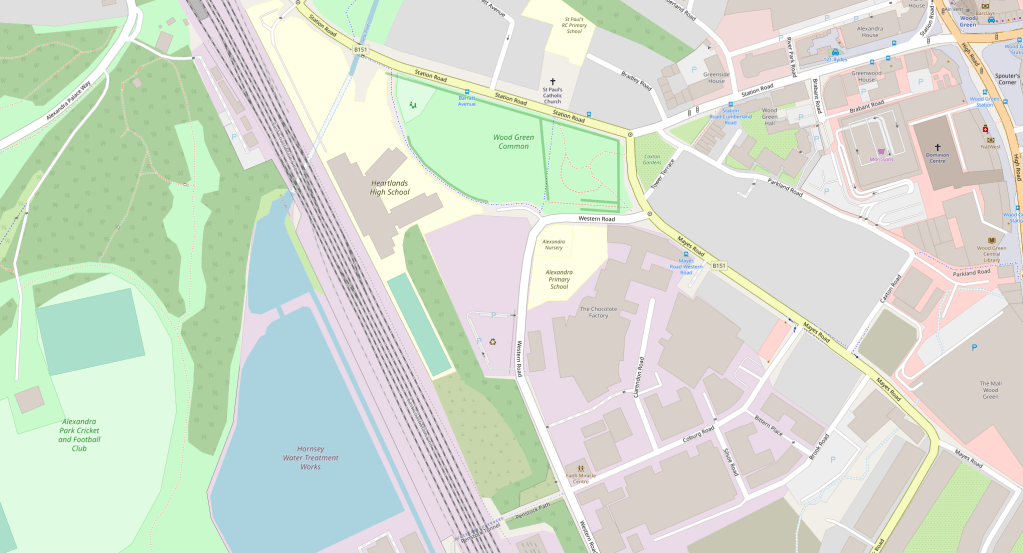

What is this vital link in our motor transport network? On the map below that’s the road running parallel to the A10 just a bit to the east, from White Hart Lane at its southern end to Wilbury Way in the north. Devonshire Hill School is shown as a yellow patch on the east side of Weir Hall, not far from the Rectory Farm Allotments.

The A10 is a high speed dual carriageway. The idea that the smooth operation of the road network requires Weir Hall Road, a simple narrow street running past homes and two schools (the second school is in Enfield, so not covered in Haringey’s report) to serve as an overflow for the A10, shows just dominant the motoring logic is within Haringey’s highways team.

Part of the tragedy – and to say tragedy is not hyperbole: we’re looking here at children’s inactivity and lack of independence, at lungs and brains impaired by particulates, and at a stomping big carbon footprint – is that a non-trivial share of the traffic on Weir Hall Road is to the two schools on it: 24% of the children at Devonshire, a community school, are driven there, probably in large part because its entrance is on a narrow road that many drivers are taking at what speed their little motors can muster, so of course many kids aren’t allowed to walk there, much less to cycle. So we have traffic generating traffic, which is what traffic does.

We see the same thing with other schools. Sometimes the finding is a simple “not suitable for a school street”, as with Devonshire; other times it leads to restricting the school street to a less busy road. I exclude here cases where the busy road is in fact a major thoroughfare. But what is a major thoroughfare, and what is not, may be in the eye of the beholder. 37% of pupils are driven to and form St Martin of Porres RC Primary School on Blake Road in Bounds Green. It is “not suitable” for a school street because

The implementation of a school street in this location would have a negative impact on the wider road network operations as Blake Road is part of the main connection between A109 and Albert Road.

“Part of the main connection” seems to mean “a rat run we use for overflow”. On Map 2, below, St Martins is the yellow patch down a long driveway off of Blake Road, just by the railway. The main connection between the A109 (Bounds Green Road) and Albert Road (B106) should be made by turning onto Durnsford Road (also B106) at Bounds Green. If that route is so busy that Google is sending drivers down Blake Road, perhaps Haringey should get behind the Enfield Council’s proposal to put a bus filter (i.e., no motors except buses) on Durnsford, between Bounds Green underground and the North Circular. I hear, though, that Haringey’s Highways Department actually opposes Enfield’s plan; I can only hope that I am misinformed.

Schools which are “suitable”, but where the most problematic street is left out of the plan because it’s too important as a rat run, include Chestnuts Primary (Black Boy Lane). Chestnuts had been rated “unsuitable” in an earlier draft of the plan but, after a couple of instances of kids being hit by cars and the intervention of parents who are also involved in an LTN initiative in the St Ann’s Ward, a way was found to make a school street on a side road by one of the school’s three entrances. Yet the real problems remain: the Black Boy Lane rat run; lack of bike paths and lack of a safe crossing on St Ann’s Road. In the same ward, West Green Primary is listed in the plan as a priority but no details are given for it; I understand that the planned school street for West Green, like that for Chestnuts, would be confined to a little side road (Termont, in this case), while the problematic rat run (Woodlands Park Road, which also passes by the Woodlands Park Children’s Centre and Nursery) is left as is.

Time now for low traffic neighbourhoods AND school streets. In all of the cases above, and many others besides, the school street solution would be improved by the creation of an LTN. Even with LTNs in those places, you would still want a school street because the LTN just stops through traffic, while the school street limits the use of the school as a destination for car trips. But, while it would be feasible simply to make parts of Weir Hall Road and Blake Road school streets to reduce the school runs there, the school street restrictions would be much less disruptive if drivers didn’t expect to be able to use those roads as rat runs in the first place. Morning school run is the busiest time of day on the roads, so it is feasible to keep non-resident traffic off those roads at those times, it can be done 24/7 with an LTN.

The Weir Hall/Devonshire School and Blake/St Martin’s School situations are relatively simple, because any traffic diverted from those rat runs would go the main roads where it should be in the first place. Cases like Chestnuts/Black Boy Lane, and West Green/Woodlands Park Road, are more complicated because they sit in systems with multiple rat runs, where closing one easily diverts traffic to another. A well-planned LTN can prevent such spill-overs, and encourage an overall reduction in traffic (including, but not limited to, the reduction in school run traffic).

Or consider Rokesly School in Crouch End. The proposed school streets would cut traffic at school run times, which would be a benefit. But the air quality at the school is rated Poor (most schools in Haringey get Medium, which is already not very healthy), and that’s not going to be fixed without filtering the roads around it; these aren’t main roads, but given the structure of the road network in the area filtering will require some planning. That brings us back to finding a way to replace the stillborn Crouch End Healthy Streets project, and to do better than the Council’s subsequent choice (contrary to the balance of consultation views) to go with pavement widening rather than a cycle track on Tottenham Lane. It’s complicated, but the nettle must be grasped.

There are many cases in the School Streets Plan where filtering traffic as part of an LTN plan would make the school street more effective, and probably cheaper. For examples, I’ll return to St Ann’s ward: for a school street on Avenue Road in front of St Ann’s CE Primary School, the School Streets Plan anticipates £26,400 for ANPR cameras and some signage. The LTN proposed by Healthy Streets St Ann’s would include a modal filter on Avenue Road. If that filter were located at the St Ann’s Road end of Avenue Road, the bit of Avenue Road in front of the school could simply be repurposed as pedestrian space, possibly eliminating the need for the camera.

Then, looking just across St Ann’s Road, we find St Marys RC Primary School. Here, the Plan anticipates £55,000, mostly for cameras on Hermitage Road (I’m guessing the difference in cost is because Avenue Road is one way while Hermitage Road is two way, so needs double the cameras). There has long been discussion of a modal filter on Hermitage to improve air quality at that school, eliminate rat runs through a nearby council estate and the adjoining neighbourhood, and improve pedestrian and cycling safety. With a filter on Hermitage, there would be vehicular access tot he school from only one direction, so the school street would not need as many cameras.

As with the Weir Hall/Devonshire School and Blake/St Martin’s School cases discussed above, these are cases where the proposed school streets are currently rat runs. Not all proposed school streets are rat runs, but where they are, the council and the community should always consider whether the rat run needs a 24/7 filter in addition to school streets measures. For St Ann’s and St Mary’s, as for Devonshire and St Martin’s, filtering should reduce driver confusion, improve compliance and reduce cost. Also, if one object is to improve school air quality, the rat run should anyway be closed throughout the school day, which the filter accomplishes.

The long and the short is that much more can be gotten from this School Streets Plan if the borough’s Highways department is on board with a serious program of low traffic neighbourhoods, and traffic reduction in general. Where a highly polluted school apparently can’t have a school street because it’s on a busy road, the solution should not be to label it “not suitable”, but to shift its case to another level of investigation, to ask how motor traffic on that busy road might be reduced. Sometimes it won’t be possible, but in a context of overall traffic reduction, and promotion of active and public transport – the context the Council says we’re in – there will sometimes be ways.

Pavement widening – really?

At two of the schools (Alexandra Park Primary and Bruce Grove Primary), school streets are to be accompanied by build-outs of the pavement “to allow social distancing”. This seems a failure of nerve, if not a misunderstanding of how the school street works: if the school street is functioning properly, the road space in front of the school is a pedestrian zone at the times when children are coming and going. It seems just a waste of money.

In the Alexandra Park case, it may be that the report’s authors recommend pavement widening because they lack confidence in the safety of the school street itself, because of need for access by businesses on Western Road. As far as I can see there are other ways in to almost all but one of these businesses from the other end of Western Road, so I’m not sure what the fuss is about. Pavement widening is a favourite fix by Haringey Highways – it’s a way of doing something for active travel without actually putting in cycle lanes, and indeed sometimes preventing future cycle lanes – and I wonder if the school streets study teams might have been exposed to this virus.

What’s the problem? Parking? Congestion? Pollution? Lack of childhood liberty?

The reports on individual schools were put together by consultants operating under time pressure, during a pandemic, with a new sort of issue to deal with. Haringey has a lot of primary schools. Not surprisingly, there are places where the description of the case and the reasoning for the recommendation don’t really seem to add up. I’ll describe a couple of cases, but before the recommendations are set in stone there really should be a process of school-by-school review.

Bounds Green Primary School has its main frontage on Park Road, with one side of the school facing the very busy Bounds Green Road. About the first of these the report says:

“A site visit highlighted that Park Road is a congestion hot spot with parents parking on the School Keep Clear markings, double yellow lines and in the middle of the road and then conducting U-turns, leading to further congestion.“

Sounds as if Park Road should be a school street, then? Well, no, because a few lines later:

“The location of the school is not suitable for a school street despite the ‘medium’ air quality. The majority of parents observed walked or cycled with their children … there were low traffic volumes observed on Park Road and therefore implementing a school street in this location is unlikely to have a significant impact on operations or air quality.”

Granted that most of the air pollution will be coming from Bounds Green Road; but what happened in the space of a few lines of the report to all of the congestion and illegal parking by parents which, if as described, will surely be having some effect on the willingness of parents to let their children walk or cycle to the school independently? It may in fact be that independent active travel by children isn’t in the remit of the report’s authors – it’s not discussed.

Safety improvements which lower the age at which parents are willing to let their children walk or cycle to school independently are important for two reasons: first, restoring to children some of the freedom which has been taken away from them in the past few decades; second, reducing school run driving by parents whose need to both take a child to school and get to work resolves into a car trip.

This is not the only way in which the report sometimes seems to overlook important benefits that school streets can bring. For many of the schools found “not suitable” for school streets, lack of congestion or lack of school-run-related parking problems are given as reasons a school street is not needed. This misses not only the active travel benefits, as just noted in the case of Bounds Green School, but also the school run’s large contribution to road traffic overall – not just in front of the school.

Sometimes, the report misses low hanging fruit. Coleridge Primary School is slated for a school street, someday, which is good. But the proposal ignores Crescent Rd, which runs between the school and Parkland Walk. Crescent already has a modal filter that stops motor traffic from joining the main road, Crouch End Hill, so perhaps it wasn’t seen as a problem. Yet the stub end of Cresenct Road, with no houses or businesses, now serves as a school run hotspot. It should not be a road, but should be made into parkland, joining up the park along Parkland Walk and the strip of park between Crouch End Hill and the school.

Enough for now!

Boroughs to the north, south, and east of Haringey have made far greater progress on low traffic neighbourhoods, school streets, and cycle infrastructure. The excuse sometimes given for this is that those other boroughs had more money: Waltham Forest (east) and Enfield (north) were two of the three London boroughs to get Mini-Holland money from TfL; the boroughs closer to the centre (Hackney, Islington and Camden) have more money from developers. And, then, having had a lot of practice and something to show for it, when it came to COVID emergency funds for active travel, those boroughs with better track records had applications that looked more credible.

I don’t think that washes. Of course the borough has money problems. But, when it comes to active transport, it has simply left a lot of money lying on the table because the borough, as an institution, has not been interested in active transport. Consider these examples:

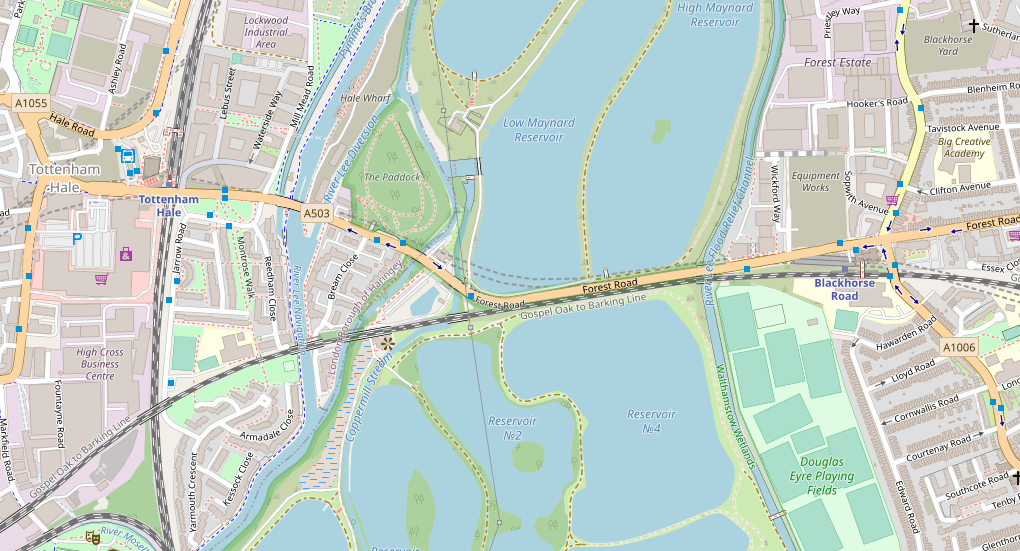

Tottenham Hale (Haringey) vs. Blackhorse Road (Waltham Forest). Two stations, Victoria Line plus surface train; both sites have large new highrise developments. Councils get money – Section 106 funds – from developers to make improvements in the area and to mitigate adverse impacts of the development. In this way, Waltham Forest got money to put in high quality cycle tracks at the Blackhorse Road junction. There’s little indication Haringey did the same at Tottenham Hale.

Getting quality cycle tracks at a big busy junction is a big deal – it’s costly, people with specialist cycle track expertise are needed for design and implementation, and invariably it takes something away from motor traffic. Most main road cycle tracks in the UK just sort of give up at big junctions, leaving cyclists to fend for themselves among turning motorists. It’s a key obstacle to the development of useful networks of safe cycle routes.

Try this experiment: starting somewhere in Waltham Forest – maybe at the William Morris Gallery in Lloyd Park – ride your bike west along Forest Road. Most of this road has segregated cycle tracks, both ways (it is currently being extended well beyond Lloyd Park to the east, including first class cycle tracks through Bell Junction, a busy crossing of two A roads). Actually, what sets it apart most dramatically from roads in Haringey is a small bit where the westbound track is not segregated, but on the roadway. The double yellow lines are accompanied by yellow kerb markings, prohibiting not just parking, but loading.

I’ve never seen this on the (rare) cycle tracks of Haringey, where the council is happy to have cyclists pushed out into the motor traffic by any driver capable of turning on the blinking hazard lights. Those yellow kerb markings are the least expensive part of the cycle track, but they’re of critical importance to creating a network that can be used safely by cyclists of all ages and abilities.

At the Blackhorse Road junction, we see the fruits of the Section 106 money from the developers of nearby tower blocks: cycle crossings, and continuing cycle tracks, in all four directions.

Continue now along Forest Road. It passes some large building works (cycle lane diverted briefly, but still safe from traffic, and continuous), then the beautiful Walthamstow Wetlands (good walking and birdwatching on both sides), and on toward Tottenham Hale. You’ll know when you reach the borough of Haringey because the cycle track first loses quality, and then disappears. The photo below shows the bit of green tarmac that’s meant to suggest a cycle track, but there’s nothing to prohibit, much less prevent, the car in front of me from driving in it.

I’m not holding my breath but, maybe, that will all be fixed as the building work at Tottenham Hale nears completion. But even if it is, you continue past the Tottenham Hale station and the big car-oriented retail complex that the council allowed to be built absurdly at a transport hub, sandwiched between high density housing developments (high density even before the new tower blocks) and nature reserves. Why allow a car magnet here? But I digress. Make your way around that car park and rejoin what is meant to be a cycle track along part of Broad Lane, the road from Tottenham Hale to Seven Sisters. This track shares the pavement: here it’s marked separately from the footway; there it suddenly becomes “shared space” where pedestrians and cyclists are expected to spontaneously agree to rules for peaceful coexistence; in part of that shared space a bus shelter sits in the middle of the path with no clear indication of how to proceed; and, at several points, side roads or driveways are given priority over the pedestrian and cycle traffic, with drivers pulling straight up and blocking the path. In Waltham Forest, cycles would be given priority; cross to our side of the Lea, and it’s cars.

The problem with the Broad Lane cycle track is not lack of money: it did not cost less than a good cycle track would have cost. The problem is that Haringey prioritises cars, both moving and parked, over other forms of transport.

Railway bridges. In 2017, Wightman Road was closed to through traffic for several months while the bridge across the Gospel Oak-Barking railway was replaced, at a cost of I don’t know how many millions of pounds to Network Rail. Residents of the area, thrilled with the sudden lack of traffic, rallied to urge that the closure be made permanent.

Now, this was actually a great opportunity for Haringey. The old bridge was perfectly safe for pedestrians and cyclists. The council could have offered to Network Rail the repurposing of the bridge for pedestrians and cyclists only, so that the costly replacement was no longer necessary, on condition that Network Rail share some of the savings with the council. That, in fact, is what the borough of Waltham Forest did in the case of two bridges over the same railway line, helping to create (and finance) two of their early Low Traffic Neighbourhoods. Here’s one of them, not far from the Blackhorse Road station:

Haringey council instead spent a substantial sum on a big study of what to do about traffic on Wightman and in the Green Lanes area overall – roughly, the wards of Harringay and St Ann’s. Many suggestions for traffic reduction measures came from the public and, of those that the council allowed into the questions on the final consultation, steps most respondents favoured included getting rid of through motor traffic on Wightman, making the southbound bus lane on Green Lanes 24/7 rather than just weekday morning commute, and getting rid of parking to make room for a northbound cycle track on Green Lanes. The council decided to do none of that, and to make minor improvements to Wightman. This was not for lack of money, but because the politics of getting rid of parking on Green Lanes were too much for the council to stomach. I wrote some blogs about it at the time: Deference to Traffic, and Deference (again) to Traffic (the titles do give away the ending, though).

By the time all of this study-and-inaction was finished, of course, the millions to replace the old railway bridge had been spent.

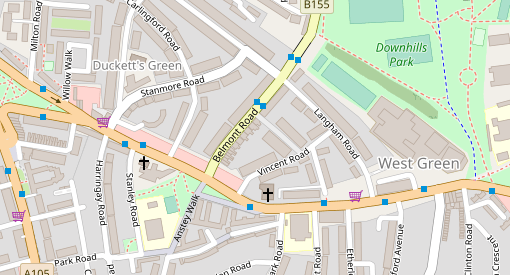

The Belmont-West Green-Langham triangle

We could say that’s all water under the bridge, but the fact is these things are ongoing. Right now, boroughs all around us are transforming neighbourhoods so that drivers can’t take rat-runs through them. COVID emergency funds were being given out to help with this process, though Haringey’s applications for such funds were turned down. But sometimes Haringey gets other funds that could be used to create low traffic neighbourhoods, if it really wanted to do so. For instance, it has just received from TfL £80,000 on some road safety improvements in this area:

Belmont Road and Langham Road have been the site of numerous injuries to pedestrians at the hands of drivers. Langham Road is an extremely busy rat-run. Langham has relatively high density rental housing and passes by one entrance to Park View Secondary School. Traffic queuing to turn from West Green Road into Langham further fouls the air, and delays buses. Stanmore Road is also a rat run.

Two or three very simple traffic filters would solve this, keeping the through traffic on the main (A & B) roads, and making both Langham and Stanmore into safe places for kids. Elimination of a few parking spaces would make space for a right turn lane from West Green to Belmont, preventing traffic delays on West Green there. Haringey Council estimates traffic filters cost about £30,000 per junction on average, but other sources put that at about £20,000. Two small low traffic neighbourhoods could be had (or at least tried) at well within the £80,000 budget for the safety project.

What’s the Haringey Council doing with the money? Putting in traffic bumps on Belmont and Langham. The cars will still come, with the SUV drivers hardly noticing the bumps and other drivers producing more noise and pollution than ever with the slow-down-speed-up rhythm that speed bumps give us.

As far as I can tell, traffic filtering options were not even considered by the council. They were not included in the consultation on the project. This will not surprise anybody who has observed the Haringey Council over time: those in the council who make decisions about roads and traffic do not like filters. They can say it’s for want of money, but they find money for speed bumps, which are not cheap.

The same thing seems to be happening with improvements to the amusingly named Cycle Superhighway 1 (a route that roughly parallels the Tottenham High Road, sometimes on the pavement but mostly on back streets). This is one of the bits of COVID emergency active travel funding that Haringey was successful at bidding for. I have not seen detailed plans (as far as I know they have not been published), but it looks as if, again, they are passing up opportunities to use those funds for filters that would serve the dual purpose of making a far better cycle route and at the same time create some people-friendly streets. I’ll get back to that when I have more information.

But while we wait to learn that, we already know enough. Yes, the council is short of funds. But that is not the reason drivers rule our streets and our air is toxic: the reason is that the people who make these decisions at the council don’t make active travel a priority and don’t make clean air a priority; they resist solutions which would confine through traffic to main roads, while making most roads safe again for children and for other people who breathe; and they resist solutions that would reduce parking and loading to make space for cycle tracks. We get a lot of fine words from the council about active travel, clean air and reduced carbon footprint, but actions speak louder, and this council’s actions speak all too clearly.

(When I say “the people who make these decisions at the council”, I’m not being coy in not naming names: I see what the council does, and write about that; who makes the calls is not something I see, and I’m not inclined to speculate.)

We all got a laugh a couple of weeks ago upon learning why Dominic Cummings, the Dick Cheney of Boris Johnson’s government, wants the UK government free to provide state aid to companies (it’s one of the principal reaons for wanting to violate the EU Exit Agreement Johnson had pushed through Parliament just last year). The reason, as Robert Peston quotes Cummings, is:

Countries that were late to industrialisation were owned/coerced by those early (to it). The same will happen to countries without trillion dollar tech companies over the next 20 years.

The most obvious response to Cummings is best put by the inimitable Marina Hyde, who asks us to imagine a friend of Cummings looking him in the eye and saying ““Mate, with the best will in the world, what on EARTH about the last six months makes you think you can build the next Apple?”

Others have allowed mere doubt about Cummings’ competence rather than denial of it, and then given him the benefit of that doubt; instead, they criticise his trillion-dollar tech company scheme on the grounds that the countries usually classed “late industrializers” – from Germany and the USA in the late 19th century to Korea in the late 20th – are often reckoned to have done pretty well for themselves, and to have avoided ownership and coercion by Britain. In this regard, though, I think Cummings assertion is entirely correct, even if (for reasons I’ll get to) his idea is bad. Britain did use its position as the first industrial power to both own and coerce much of the world, and it did so successfully for over a century. And Britain’s success in this does offer some parallels with America’s, and the trillion-dollar tech companies of the Silicon Valley and Seattle, today. But does that mean Britain can, or should, try to follow that model today? Let me tell you why not.

From the late 18th century through the early 20th, Britain strove to keep its industrial head start by protecting the position of its manufacturers in international markets, in ways familiar to any student of history. For many decades, when it was the workshop of the world and controlled most of the cutting edge technologies, it forbade both the export of industrial machinery and the emigration of people who knew anything about making it. Eventually, the secrets leaked out anyway and Britain began to lose its manufacturing monopolies to rivals like Germany and the USA. Britain responded by building a larger empire, so that the sun never set on its captive market. Within the empire there was a strict division of labor, with manufactured products coming from the home country; parts of the empire had already developed internationally competitive manufacturing industries, and those had to go – India’s textile and shipbuilding industries, for example, were destroyed so that they would no longer threaten Britain’s industrial (and military) monopoly. So, yes, plenty of control and coercion, as Cummings says.

Today, the international monopolists are American the tech giants. These giants – the trillion or near-trillion dollar companies – are not the foremost technological innovators, but are companies which have become as rich by carving out monopolies in software and the Web, digital gardens large or small with walls to keep competitors out. Google dominates search, Amazon online retail, Microsoft office applications and personal computer operating systems, Google and Facebook online advertising, Google and Apple phone apps, and so on.

It is important to distinguish between what these tech giants have done, and technological innovation. There are many, many tech companies in the world, but only four (Google, Apple, Amazon and Microsoft) at or near the trillion dollar mark in market capitalization (Facebook is also very valuable, the fifth most valuable tech company, but in this league it’s mini-me). Take phone apps as an example. Google’s and Apple’s phone operating systems are based on sophisticated open source software others have written and given away; the phones, marvels of electronics and miniaturization, are made by others; the apps on the phones are written and sold by thousands of individuals and companies around the world; Google and Apple, in their positions as gatekeepers, take generous cuts from each sale of an app. Many, many tech companies are involved in phones, phone software and phone apps, but only two are anything close to being trillion dollar companies; that’s because they’ve established strong monopoly positions, just as Britain did for its world-serving workshop about two hundred years ago.

When he says “trillion-dollar tech companies”, that is the sort of business Cummings wants to get.

Cummings’ fascination with trillion-dollar tech companies, then, does fit nicely with the characteristic Brexiteer’s nostalgia for empire; he is seeing, accurately, today’s analogue. The question then is, should the UK try to join in the game America is playing?

Some would say not on the grounds that, in the long run, the imperial-monopoly strategy left Britain weak. To succeed in a world dominated by Britain, its late-industrialist rivals devised superior industrial systems: Britain was out-produced by the USA, out-engineered by Germany, out-managed by many countries; sheltered behind its imperial market and the returns from previous overseas investments, it clung to a strong pound to prop up the value of a diminishing stream of income from overseas. Many would say that the US is doing something analogous today, its considerable diplomatic powers devoted to protecting Silicon Valley and a few other sectors, at the expense of hollowing out the rest of its industries (see Dani Rodrik on this point). But is that really failure? Nothing lasts forever; Britain had a very good run, as now America has had as well.

But Britain is not going to be able to do it again.

One thing Cummings has right is that if the UK were to attempt this strategy, it’s probably good that it’s left the European Union, because Brussels – the European Commission and all those nasty bureaucrats – are the only force on the planet making a serious effort to tame and regulate the monopoly power of Big Tech. That’s not the game Cummings wants to play.

But, being out of the EU leaves the UK with the problem of having a relatively small domestic market. The classic late industrializer response to Britain’s power was to use a protected domestic market as a greenhouse in which to develop new firms, which can then compete globally when they’re big and strong. China is doing exactly that for its own web giants. The UK domestic market, however, is nowhere near big enough to do what China is doing.

An alternative version says that the UK’s imagined tech titans would neither be exposed at birth to the fierce storms of global competition, nor confined in the UK’s too-small domestic market, because the post-Brexit UK will somehow become part of a new Atlantic or Anglo-zone economy – Airstrip One, as Orwell had it. This vision of course gets a reality check every time Nancy Pelosi has to remind the British government that it won’t have any trade deal with the US if it allows its Brexit extremism to undermine the Good Friday Agreement. But let’s say for the sake of argument that the government can solve the problem of creating a hard border around the UK without creating one on the island of Ireland and, following further triumphs of diplomacy, the UK’s emerging tech companies find themselves within a very large protected market which includes the United States.

Now, one place Cummings’ thinking does make contact with reality is in understanding that the UK – and in particular, London, Cambridge and the Southeast of England generally – does have great strengths in the tech giants’ sectors – software, web applications, business services; it has the skills, the financing, the start-ups, and the very close links with the American tech giants themselves. It is already part of that industrial eco-system. Surely all it lacks is to itself be the home base of couple of very rich companies? Perhaps, as the West Coast becomes uninhabitable due to smoke from forest fires, opportunities to form the next generation of tech monopolies will shift back to the mother country?

Many places, though, offer themselves up to become the new center of tech gravity, should it ever shift; if there were a new center and it were not in Asia, it would more likely be someplace else in the United States; Boston, New York, or even North Carolina would be more likely than London, even if the UK were part of a seamless Atlantic market. That’s because UK has never been good at building big businesses. From the late nineteenth century onwards, the US, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, France, Sweden, and Switzerland all have been better at building big companies with sustained internal programs of innovation and investment, and with global reach; in recent decades, Korea and China have joined those ranks. We have seen this in steel, chemicals and electrical equipment in the 1870s-1890s; in automobiles and other mass production industries in the early to mid twentieth century; the computer, semiconductor and telecommunications industries in the late twentieth century. We see it again in the software, web and business service giants of today.

The roots of Britain’s relative weakness at building and sustaining big companies lie in institutions which served it well as an empire: powerful financial institutions which invest with a focus on short-term gains; financial and govenment decisions in the hands of a narrow national elite with generalist educations and little grounding in the particulars of any industry – but born to rule; companies which stay light on management, on capital investment, on training, and on research and development.

That these proclivities stay stubornly in place is a classic problem of path dependency, of the interlocking and mutually supporting nature of any set of established institutions which restrict the range of choices as things change. However you understand the reasons, however, the fact is that the US is far, far better at building and sustaining big companies than the UK, and if the UK is operating within the US sphere it is not the UK that will be the home of the trillion dollar companies.

Is it a bad thing that the UK will not become the home of several trillion dollar tech companies? Not really. America’s tech empire, like Britain’s empire of yore, is a system of appropriation which makes one corner of the world rich at the expense of the rest. And it can’t even be said that it makes the US, as a country, rich: within the US, these tech monopolists and their financial and political enablers enrich particular places – particular cities and regions – at the expense of the rest of the country, as Maryann Feldman, Simona Iammarino and I discuss (with lots of nice maps) in this paper. There’s a similar pattern in the UK, with divides between South and North; between those paid well enough to live well in overpriced gentrifying tech+finance cities, and everybody else. Becoming home to one or more trillion-dollar tech companies would only exacerbate these divides. Cummings and his ilk would do well in that bargain, but for the UK as a whole it would not be a good thing, so we can be glad that Cummings is wrong.

Unfortunately, with Cummings’ strategy out the window, we are left with the question of what sort of post-Brexit economic strategy would work for the UK. I can’t answer that one.

My friend Don Cushman is one of the few people I know who actually liked the third Godfather movie, but this has to do with Don’s views about the Vatican and all its works, views hanging over from his years as a seminarian. On that topic, I preferred Don’s 1996 novel Visitation, though perhaps Coppola had simply set too high a bar with I and II. About the Vatican I know almost nothing beyond what I see in such popular sources, but I did know an obscure trivium, namely that the American magazine editor Norman Cousins had once been sent by JFK to feel out both the pope (John XXIII) and Nikita Khrushchev about some matters of world peace. I knew this from reading the dust jacket of the book Cousins wrote about it; in the early 1970s, I worked for a while for an organization called the World Federalists, in whose ranks Cousins was a luminary, and our storeroom had piles of unsold copies. “I knew Norman Cousins”, I said.

Now this is a name I should have dropped long ago, since most of the people who would be impressed by it are by now no longer with us. Timing has never been my forte. Don and his wife Joann, however, being American intellectuals somewhat older than myself, were the right audience and it seemed to make an impression. Joann could probably drop the names of most of the civil rights leaders of the early 1960s if she wanted, and then I’d use them second hand, but she’s too modest and self-assured to help out in that way.

Cousins was much better about sharing names. Having been evidently bored in a meeting he said, when it came to a break, like a player hoping to be asked to bring out the cards, “Have I told you about my meeting with Arafat?” Arafat was then, as they used to say of Dick Cheney, in a secure location, presumably somewhere in Lebanon. The US government was not openly talking to him; somebody had asked Cousins to do so. We sat spellbound. All I remember of the story – probably, all he could tell us – had to do with being blindfolded and driven around for a while so that he would have no idea where he was when the meeting took place.

After dropping his name I figured I ought at least to read Cousins’ book, The Improbable Triumvirate. After fifty years, nearly-new copies remain available at remarkably reasonable prices, as if the World Federalists’ storeroom had just been emptied. It’s a funny book, for two reasons. One is that the famous literary editor had written something which seems to have been composed mainly from his old appointment books and memoranda from meetings – the clunkiest narrative I’ve ever read. The other is that the big character in the book is Cousins himself, the only real energy amongst all these minutes of meetings is him setting both Kennedy and Khrushchev right (he doesn’t actually meet with the Pope, and whatever he said to Vatican diplomats can’t leave the same impression). Underneath this is a remarkable story – and the behest of JFK, he’s staying with Khrushchev at his Black Sea retreat, talking about capitalism, communism, war and peace, I’m all ears – but the surface is just an advertisement for Cousins.

Luther Evans could drop a name with more finesse. I have just dropped his, a name which the passage of time might have rendered worthless were it not for Wikipedia, which will fill you in if your really must know. Working in the cause of world peace we often found, as in any political organization, that our most menacing enemies were rivals within, and some of us youngsters were perhaps rash in our plans for thwarting one such person. “I am reminded of something Macleish once said to me”, said Luther to us: “don’t kick a dog ’til you know it’s dead.”

Location can help. Walking through Berkeley with Stuart Hampshire and Nancy Cartwright, we came across a notice – as one would, those days, in Berkeley – for some event involving Ivan Illich. “Illich”, quoth Stuart, “old chum of mine. Went a bit off the rails with that Medical Nemesis stuff, I’m afraid.” And then – I want to make this the same walk, though that seems too lucky – upon seeing a notice for an event celebrating EE Cummings, almost the same: “old chum of mine. Terrible reactionary, really.” These opportunities would not have presented themselves had we been walking through Omaha. But then, we would not have been.