The death of writing, gradually then suddenly: new post on Substack

https://frederickguy.substack.com/p/watching-as-reading-and-writing-become

The death of writing, gradually then suddenly: new post on Substack

https://frederickguy.substack.com/p/watching-as-reading-and-writing-become

New blog posts will appear on Substack:

As a business deal, Trump’s tariffs seem to make sense for Trump and Trump only: Trump, the shake-down artist. As many have pointed out, what the President gets out of this is a queue of CEOs begging him for exemptions; in return all he’ll ask is loyalty, public admiration and some display of … generosity. As economic policy for the country of which Trump happens to be president it is of course crazy – the tariffs are Smoot-Hawley Mark II, with some amplifying factors: economic activity in today’s world crosses borders a lot more than it did in 1930; nations are more specialized and thus dependent on exports and imports; production processes skip back and forth across borders, so that trade barriers will affect almost every manufactured product, even if made for domestic consumption; also, Trump’s mafia-boss shakedown mode, himself imposing and revoking tariffs personally as President, adds greatly to economic uncertainty, which will further undermine both capital investment and the purchase of consumer durables. So it’s mad, economically, we know that. That’s how mafias work, and how mafia states work: most people are losers, but the boss does well.

Trump’s tariffs and digital platforms

Still, Trump does have some constituents whose welfare he is concerned with. At this point his circle of concern may be small, but it does seem to include the oligarchs who back him, in particular those controlling big digital platforms: they are, now, his political base, those who stood closest to him, wives at their sides, while he was sworn into office. Are their interests threatened by a trade war? Spencer Hakimian hints at this risk in a post on ex-Twitter (sadly he doesn’t seem to be on Bluesky yet):

I reproduce this post because it offers a simple picture of America’s trading relationship with Europe, and for that matter with the rest of the world: the US exports less in the way of material things, more in the way of intangibles. A lot of the intangibles – what Hakimian calls “tech software and financial services” – are things controlled by big digital platforms, delivered over the Web: social media; internet search; the two smartphone platforms; the three major payment platforms (Visa, Mastercard and Paypal are behind Apple/Amazon/Google/Microsoft/Meta in market capitalization, but are still among the world’s most valuable companies); the biggest TV/movie/general video streaming platforms; the great suppliers of general purpose software (Microsoft, Adobe, Oracle…); Amazon’s everything store.

So is Trump, with his rash tariffs, endangering the lucrative platform business? At first look it appears not, but Europe could make it so.

It first appears not, because most of the platforms’ revenue isn’t from trade – it’s simply repatriated profits from overseas subsidiaries which export almost nothing from the United States; in other cases it is trade in digital services and as such exempt from tariffs under a WTO moratorium that’s been in place since 1998. Raising tariffs doesn’t hurt Amazon, or Visa, or Netflix.

The tariff exemption for streamed services may not last, though: large developing countries such as India and Indonesia have long opposed it, and will push again to end it in 2026. But the far bigger, and tougher, issue is the power of platforms when they aren’t selling anything across borders – they might sell advertising for their global platform locally in each country, or license rights to subsidiaries located there; indeed, much of what is now streamed internationally could probably also be handled that way, if the exemption which now protects them is lost, and could thus remain tariff-free. In this light Trump’s tariff tantrum might make some kind of avaricious sense – the US can put steep levies on imports of manufactured products and raw materials, while American digital platforms would continue to rake in revenues from around the world, tariff-free.

All countries will, of course, put up retaliatory tariffs on goods. This is necessary but just creates an unpleasant standoff in those markets where tariffs apply, while America’s platform oligarchs thrive unmolested.

Hit him where it hurts: Europe can take the fight to the platforms

Europe is in a position to do something about the power of the platforms: this would be good for European consumers and businesses, and bad for Trump. Which is to say, win-win.

The global dominance and immense profitability of the American platforms has been possible not just because those firms moved first to use web technologies, but also because governments have allowed it. To date, the only serious challenge has come from China, which has shut out many of the American platforms and fostered its own domestic Web giants, such as Tencent and Alibaba. Mario Draghi, in his influential report to the European Commission, advocates the creation of European mega-platform companies. Draghi writes in connection with concerns about European labor productivity – the value of output per hour of labor – which has not kept up with that in the US. He notes that the growth of America’s productivity advantage is due to “tech”. This is true and yet it also shows why productivity is, in this case, a very bad guide to policy: a highly profitable monopoly of course has high labor productivity, because the monopoly profits are part of value added – if you divide Microsoft’s profit by its number of employees, each of them looks quite productive. Europe’s economy lacks such big monopolies and is thus more competitive, which is a good thing for all but any would-be European oligarchs.

Moreover, even if Europe wanted them, it’s not clear it could create mega-platforms. The existing platforms benefit, in their nature, from huge scale economies. Replicating them would be impossible in head-to-head competition; China avoided head-to-head competition by simply shutting out the American platforms, but the China strategy is incompatible with an open society, and would also be economically destructive if replicated in Europe. (Europe could get serious about expanding its digital technology sectors, with an initiative such as Eurostack, but that does not require a monopolistic platform.)

What Europe can do instead is to get serious about instilling openness and competition in the markets now dominated by platforms. Platforms are network services – that is what gives them their scale economies and their power. A century and more ago, earlier generations of network services – railroads, electric power, landline telephones, and so on – were brought under either public ownership or strict regulation everywhere in the world, by governments of both right and left, both in countries with market economies and in those styled communist. The reason governments everywhere made that choice, independently of each other and for numerous different networks, is that these networks were essential for the modern economy, and no government could afford to let an economically essential network be held ransom by some robber baron.

The same goes for web services today. Why should you need to use Microsoft’s or Adobe’s proprietary product to make the files you create reliably readable by others? Why should you need to subscribe to multiple streaming services in order to have access to the occasional movie or sporting event of your choice? Why should the major online public marketplace, connecting buyers and sellers, be operated by a single extremely profitable company? Because our governments have allowed it, that is the beginning and end of the story.

What the platform oligarchs fear most is this: that parts of their platforms will be subjected to market competition, and other parts where competition is not feasible will become public utilities operating on the common carrier principal. To avoid that outcome, the oligarchs – most of them former liberals – are apparently happy to live in a fascist state. The reason they pivoted so decisively behind Trump in last year’s election is that the Biden administration had finally reversed America’s nearly fifty year retreat from anti-trust enforcement: an astonishing team including Lina Khan chairing the Federal Trade Commission, Jonathan Kanter heading the Justice Department’s Anti-Trust Division, Rohit Chopra heading the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and Tim Wu as Special Assistant to the President for Technology and Competition Policy, were at work battling the platforms in the American courts. So the oligarchs backed Trump, and won.

But won only in America. And now Trump is trying to bully the rest of the world on trade (and possibly on supporting the dollar), with the platform oligarchs at his back. Europe is a very large market, and the European Commission has responsibility for market competition throughout the EU. Anything Europe does to bring the platforms to heel can be – and will be – copied by other governments around the world: this is where Trump and his oligarchs can be beaten. The Commission does have ongoing efforts to bring the platforms into competitive markets – enough to make both Trump and the platform oligarchs upset, but far too slow, and on too many occasions too soft. Now that Trump has decided that Europe is his enemy, and has launched his crazy tariffs on the world, it is time for Europe to hit Trump, and his oligarchs, where it hurts.

Boroughs to the north, south, and east of Haringey have made far greater progress on low traffic neighbourhoods, school streets, and cycle infrastructure. The excuse sometimes given for this is that those other boroughs had more money: Waltham Forest (east) and Enfield (north) were two of the three London boroughs to get Mini-Holland money from TfL; the boroughs closer to the centre (Hackney, Islington and Camden) have more money from developers. And, then, having had a lot of practice and something to show for it, when it came to COVID emergency funds for active travel, those boroughs with better track records had applications that looked more credible.

I don’t think that washes. Of course the borough has money problems. But, when it comes to active transport, it has simply left a lot of money lying on the table because the borough, as an institution, has not been interested in active transport. Consider these examples:

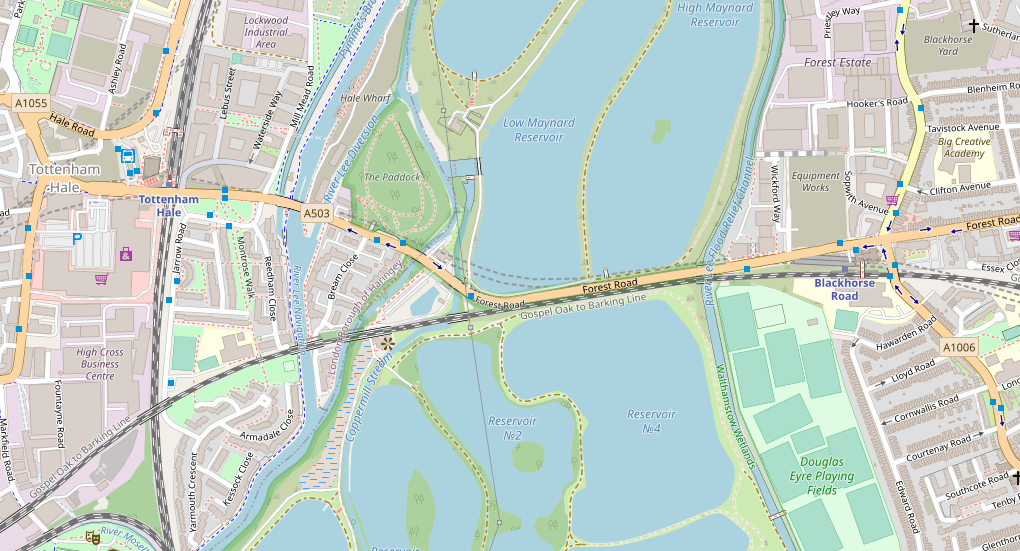

Tottenham Hale (Haringey) vs. Blackhorse Road (Waltham Forest). Two stations, Victoria Line plus surface train; both sites have large new highrise developments. Councils get money – Section 106 funds – from developers to make improvements in the area and to mitigate adverse impacts of the development. In this way, Waltham Forest got money to put in high quality cycle tracks at the Blackhorse Road junction. There’s little indication Haringey did the same at Tottenham Hale.

Getting quality cycle tracks at a big busy junction is a big deal – it’s costly, people with specialist cycle track expertise are needed for design and implementation, and invariably it takes something away from motor traffic. Most main road cycle tracks in the UK just sort of give up at big junctions, leaving cyclists to fend for themselves among turning motorists. It’s a key obstacle to the development of useful networks of safe cycle routes.

Try this experiment: starting somewhere in Waltham Forest – maybe at the William Morris Gallery in Lloyd Park – ride your bike west along Forest Road. Most of this road has segregated cycle tracks, both ways (it is currently being extended well beyond Lloyd Park to the east, including first class cycle tracks through Bell Junction, a busy crossing of two A roads). Actually, what sets it apart most dramatically from roads in Haringey is a small bit where the westbound track is not segregated, but on the roadway. The double yellow lines are accompanied by yellow kerb markings, prohibiting not just parking, but loading.

I’ve never seen this on the (rare) cycle tracks of Haringey, where the council is happy to have cyclists pushed out into the motor traffic by any driver capable of turning on the blinking hazard lights. Those yellow kerb markings are the least expensive part of the cycle track, but they’re of critical importance to creating a network that can be used safely by cyclists of all ages and abilities.

At the Blackhorse Road junction, we see the fruits of the Section 106 money from the developers of nearby tower blocks: cycle crossings, and continuing cycle tracks, in all four directions.

Continue now along Forest Road. It passes some large building works (cycle lane diverted briefly, but still safe from traffic, and continuous), then the beautiful Walthamstow Wetlands (good walking and birdwatching on both sides), and on toward Tottenham Hale. You’ll know when you reach the borough of Haringey because the cycle track first loses quality, and then disappears. The photo below shows the bit of green tarmac that’s meant to suggest a cycle track, but there’s nothing to prohibit, much less prevent, the car in front of me from driving in it.

I’m not holding my breath but, maybe, that will all be fixed as the building work at Tottenham Hale nears completion. But even if it is, you continue past the Tottenham Hale station and the big car-oriented retail complex that the council allowed to be built absurdly at a transport hub, sandwiched between high density housing developments (high density even before the new tower blocks) and nature reserves. Why allow a car magnet here? But I digress. Make your way around that car park and rejoin what is meant to be a cycle track along part of Broad Lane, the road from Tottenham Hale to Seven Sisters. This track shares the pavement: here it’s marked separately from the footway; there it suddenly becomes “shared space” where pedestrians and cyclists are expected to spontaneously agree to rules for peaceful coexistence; in part of that shared space a bus shelter sits in the middle of the path with no clear indication of how to proceed; and, at several points, side roads or driveways are given priority over the pedestrian and cycle traffic, with drivers pulling straight up and blocking the path. In Waltham Forest, cycles would be given priority; cross to our side of the Lea, and it’s cars.

The problem with the Broad Lane cycle track is not lack of money: it did not cost less than a good cycle track would have cost. The problem is that Haringey prioritises cars, both moving and parked, over other forms of transport.

Railway bridges. In 2017, Wightman Road was closed to through traffic for several months while the bridge across the Gospel Oak-Barking railway was replaced, at a cost of I don’t know how many millions of pounds to Network Rail. Residents of the area, thrilled with the sudden lack of traffic, rallied to urge that the closure be made permanent.

Now, this was actually a great opportunity for Haringey. The old bridge was perfectly safe for pedestrians and cyclists. The council could have offered to Network Rail the repurposing of the bridge for pedestrians and cyclists only, so that the costly replacement was no longer necessary, on condition that Network Rail share some of the savings with the council. That, in fact, is what the borough of Waltham Forest did in the case of two bridges over the same railway line, helping to create (and finance) two of their early Low Traffic Neighbourhoods. Here’s one of them, not far from the Blackhorse Road station:

Haringey council instead spent a substantial sum on a big study of what to do about traffic on Wightman and in the Green Lanes area overall – roughly, the wards of Harringay and St Ann’s. Many suggestions for traffic reduction measures came from the public and, of those that the council allowed into the questions on the final consultation, steps most respondents favoured included getting rid of through motor traffic on Wightman, making the southbound bus lane on Green Lanes 24/7 rather than just weekday morning commute, and getting rid of parking to make room for a northbound cycle track on Green Lanes. The council decided to do none of that, and to make minor improvements to Wightman. This was not for lack of money, but because the politics of getting rid of parking on Green Lanes were too much for the council to stomach. I wrote some blogs about it at the time: Deference to Traffic, and Deference (again) to Traffic (the titles do give away the ending, though).

By the time all of this study-and-inaction was finished, of course, the millions to replace the old railway bridge had been spent.

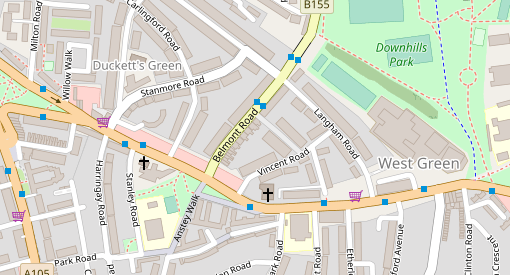

The Belmont-West Green-Langham triangle

We could say that’s all water under the bridge, but the fact is these things are ongoing. Right now, boroughs all around us are transforming neighbourhoods so that drivers can’t take rat-runs through them. COVID emergency funds were being given out to help with this process, though Haringey’s applications for such funds were turned down. But sometimes Haringey gets other funds that could be used to create low traffic neighbourhoods, if it really wanted to do so. For instance, it has just received from TfL £80,000 on some road safety improvements in this area:

Belmont Road and Langham Road have been the site of numerous injuries to pedestrians at the hands of drivers. Langham Road is an extremely busy rat-run. Langham has relatively high density rental housing and passes by one entrance to Park View Secondary School. Traffic queuing to turn from West Green Road into Langham further fouls the air, and delays buses. Stanmore Road is also a rat run.

Two or three very simple traffic filters would solve this, keeping the through traffic on the main (A & B) roads, and making both Langham and Stanmore into safe places for kids. Elimination of a few parking spaces would make space for a right turn lane from West Green to Belmont, preventing traffic delays on West Green there. Haringey Council estimates traffic filters cost about £30,000 per junction on average, but other sources put that at about £20,000. Two small low traffic neighbourhoods could be had (or at least tried) at well within the £80,000 budget for the safety project.

What’s the Haringey Council doing with the money? Putting in traffic bumps on Belmont and Langham. The cars will still come, with the SUV drivers hardly noticing the bumps and other drivers producing more noise and pollution than ever with the slow-down-speed-up rhythm that speed bumps give us.

As far as I can tell, traffic filtering options were not even considered by the council. They were not included in the consultation on the project. This will not surprise anybody who has observed the Haringey Council over time: those in the council who make decisions about roads and traffic do not like filters. They can say it’s for want of money, but they find money for speed bumps, which are not cheap.

The same thing seems to be happening with improvements to the amusingly named Cycle Superhighway 1 (a route that roughly parallels the Tottenham High Road, sometimes on the pavement but mostly on back streets). This is one of the bits of COVID emergency active travel funding that Haringey was successful at bidding for. I have not seen detailed plans (as far as I know they have not been published), but it looks as if, again, they are passing up opportunities to use those funds for filters that would serve the dual purpose of making a far better cycle route and at the same time create some people-friendly streets. I’ll get back to that when I have more information.

But while we wait to learn that, we already know enough. Yes, the council is short of funds. But that is not the reason drivers rule our streets and our air is toxic: the reason is that the people who make these decisions at the council don’t make active travel a priority and don’t make clean air a priority; they resist solutions which would confine through traffic to main roads, while making most roads safe again for children and for other people who breathe; and they resist solutions that would reduce parking and loading to make space for cycle tracks. We get a lot of fine words from the council about active travel, clean air and reduced carbon footprint, but actions speak louder, and this council’s actions speak all too clearly.

(When I say “the people who make these decisions at the council”, I’m not being coy in not naming names: I see what the council does, and write about that; who makes the calls is not something I see, and I’m not inclined to speculate.)

My friend Don Cushman is one of the few people I know who actually liked the third Godfather movie, but this has to do with Don’s views about the Vatican and all its works, views hanging over from his years as a seminarian. On that topic, I preferred Don’s 1996 novel Visitation, though perhaps Coppola had simply set too high a bar with I and II. About the Vatican I know almost nothing beyond what I see in such popular sources, but I did know an obscure trivium, namely that the American magazine editor Norman Cousins had once been sent by JFK to feel out both the pope (John XXIII) and Nikita Khrushchev about some matters of world peace. I knew this from reading the dust jacket of the book Cousins wrote about it; in the early 1970s, I worked for a while for an organization called the World Federalists, in whose ranks Cousins was a luminary, and our storeroom had piles of unsold copies. “I knew Norman Cousins”, I said.

Now this is a name I should have dropped long ago, since most of the people who would be impressed by it are by now no longer with us. Timing has never been my forte. Don and his wife Joann, however, being American intellectuals somewhat older than myself, were the right audience and it seemed to make an impression. Joann could probably drop the names of most of the civil rights leaders of the early 1960s if she wanted, and then I’d use them second hand, but she’s too modest and self-assured to help out in that way.

Cousins was much better about sharing names. Having been evidently bored in a meeting he said, when it came to a break, like a player hoping to be asked to bring out the cards, “Have I told you about my meeting with Arafat?” Arafat was then, as they used to say of Dick Cheney, in a secure location, presumably somewhere in Lebanon. The US government was not openly talking to him; somebody had asked Cousins to do so. We sat spellbound. All I remember of the story – probably, all he could tell us – had to do with being blindfolded and driven around for a while so that he would have no idea where he was when the meeting took place.

After dropping his name I figured I ought at least to read Cousins’ book, The Improbable Triumvirate. After fifty years, nearly-new copies remain available at remarkably reasonable prices, as if the World Federalists’ storeroom had just been emptied. It’s a funny book, for two reasons. One is that the famous literary editor had written something which seems to have been composed mainly from his old appointment books and memoranda from meetings – the clunkiest narrative I’ve ever read. The other is that the big character in the book is Cousins himself, the only real energy amongst all these minutes of meetings is him setting both Kennedy and Khrushchev right (he doesn’t actually meet with the Pope, and whatever he said to Vatican diplomats can’t leave the same impression). Underneath this is a remarkable story – and the behest of JFK, he’s staying with Khrushchev at his Black Sea retreat, talking about capitalism, communism, war and peace, I’m all ears – but the surface is just an advertisement for Cousins.

Luther Evans could drop a name with more finesse. I have just dropped his, a name which the passage of time might have rendered worthless were it not for Wikipedia, which will fill you in if your really must know. Working in the cause of world peace we often found, as in any political organization, that our most menacing enemies were rivals within, and some of us youngsters were perhaps rash in our plans for thwarting one such person. “I am reminded of something Macleish once said to me”, said Luther to us: “don’t kick a dog ’til you know it’s dead.”

Location can help. Walking through Berkeley with Stuart Hampshire and Nancy Cartwright, we came across a notice – as one would, those days, in Berkeley – for some event involving Ivan Illich. “Illich”, quoth Stuart, “old chum of mine. Went a bit off the rails with that Medical Nemesis stuff, I’m afraid.” And then – I want to make this the same walk, though that seems too lucky – upon seeing a notice for an event celebrating EE Cummings, almost the same: “old chum of mine. Terrible reactionary, really.” These opportunities would not have presented themselves had we been walking through Omaha. But then, we would not have been.

The lack of safe space for cycling on Green Lanes, the imposition of rat-run status on Wightman Road, the tortoise pace of buses on Green Lanes … all are due to two things: parking and loading on Green Lanes, and traffic going in and out of the Arena Shopping Park (Sainsburys/McDonald’s/Homebase).

There is now a recognized need for quick creation of a safe cycling network as the COVID lockdown eases: people are afraid to ride buses or trains, there’s not space on the road for more cars, and many people – most people, in Haringey – don’t have cars anyway. Plans are mooted for emergency cycle tracks, some of which could be made permanent. Is it going to become safe to cycle on Green Lanes?

A ray of hope comes from Transport for London’s Analysis on Temporary Strategic Cycle Network, part of its larger Streetspace for London package. There’s a map there showing existing cycle routes, and proposed new ones; the new ones are colour-coded to show Highest-, High-, and Medium Priority. There are two new routes shown in the borough of Haringey which get the Highest Priority rating. One of those routes comes over Couch End Hill from Kentish Town via Archway; the other is Green Lanes.

Green Lanes has, despite truly fearful traffic and no cycle tracks, become a major cycle route anyway; to the north, Enfield has installed a segregated cycle track on Green Lanes; to the south, Hackney is preparing one. Will the missing link through Harringay and Wood Green now be found? You can register your views by adding a comment, or a “like” on existing comment, on this great map the Council has posted.

Please do it, and also contact the councillors in your ward: it’s not to be taken for granted that the Council will solve the Green Lanes problem. Consider: on 2nd June Haringey Council followed up TfL’s announcement with its own on Active travel to aid social distancing. Go to that link and, towards the bottom of the page you’ll find a positive note from Councillor Kirsten Hearn, Cabinet Member for Climate Change & Sustainability (her portfolio includes Strategic Transport), telling us

… we are working in partnership with TfL to provide more active travel options through temporary walking and cycling facilities in Haringey as part of a funding bid … We will also aim to bring forward east to west and north to south cycling routes, so that more residents can be confident that cycling is a safe, clean and efficient way to get around and have also identified low traffic neighbourhoods to discourage use of cars.

Hearn’s message is excellent, though general. What worries me is what is included in (and what is missing from) the specifics at the top of the page, in the unsigned announcement from Haringey Council. The announcement mentions three particular cycle routes, but neither of TfL’s Highest Priority ones. They mention improvements to CS (“Cycle Superhighway”) 1, which meanders more or less parallel to Tottenham High Road; the proposed CS2 from Tottenham Hale to Camden Town, which the TfL document gives High (not Highest) Priority; and “Quietway” 10, which goes from Finsbury Park, over the rather steep hill between Stroud Green and Crouch End, and on to Bowes Park. All are worthy, but why are TfL’s highest priorities left out?

Now, in the past, in the bad old days, Haringey Council promoted Quietway 10 as the alternative to a cycle route on Green Lanes or Wightman Road. Anybody who rides a bike and considers both the topography of Quietway 10 and the paucity of places to take a bike across the railway knows that this is not serious, and that anybody who does propose Quietway 10 as a substitute for a Green Lanes cycle route either is not well informed or is taking the piss.

Thus the Council’s failure to mention Green Lanes worries me. It does not surprise me, though. The Haringey Council has long been institutionally reluctant to face up to the problems created by traffic on Green Lanes. A few years back it spent a large sum on a study of the problem and in the end found that all solutions were impractical. Times do change, and I am confident that at this point there are mixed views of the question both among elected members of the Council, and among Council officers. But the failure to mention the most obvious and important route while still name-checking Quietway 10 says to me that this battle is far from over. Hence, my pitch to you here.

Green Lanes gets heavily congested in the stretch between Manor House and St Ann’s Rd. Beyond the general sea of motor traffic in which we live, there are two specific reasons for this congestion. One is that some years ago the Council allowed the construction of a traffic magnet in the form of the Arena Shopping Park – Sainsburys, McDonald’s (complete with drive-thru), and a collection of other chain stores. All of these chains are operating on business models which require surrounding neighbourhoods to subsidize their corporations by bearing the burdens of traffic congestion, road hazard and bad air produced by people each driving their ton of steel to pick up a few groceries, or a single burger. This is not the best way to get groceries or burgers to people in a place as dense as Haringey, and it should be shut down when and if possible (permits or leases or something do expire in the not terribly distance future, I hear); in the meantime, the Council and TfL should get tough on the traffic flows. For instance, they could:

That’s half the problem, but only half. The other half is parking and loading on Green Lanes itself: loading and parking needs to be moved onto side streets or – in the case of loading – given very restricted hours.

Most people travelling along Green Lanes, and most customers of the businesses there, go by foot, bus or bike. Buses sit in traffic, cyclists take their lives in their hands – or, in most cases, just don’t ride. It’s beyond a joke. The space required to solve these problems will not, cannot, be obtained without getting parking and loading off of that road. (It’s more complicated, actually, than just space: drivers pulling in and out of roadside parking spaces, or driving slowly looking for spaces, slow things down a lot.)

You might say “but why Green Lanes – couldn’t we just put the cycle route down Wightman Road?” Well, we could – it’s not quite as good, both because of hills and because it doesn’t meet up with the Green Lanes route used by Enfield and planned by Hackney, but it would be better than what we have. The problem: to make Wightman a good cycle route you would need to filter it to take the through motor traffic off of it, and doing that puts extra traffic onto Green Lanes; not much, but in its present state Green Lanes already has more traffic than it can accomodate. To filter Wightman without making Green Lanes worse, we need to sort parking, loading and the traffic from Arena Shopping Park, anyway – there’s no getting around it.

The merchants of Green Lanes have always protected parking and loading on Green Lanes itself. It is of course well established that merchants over-estimate the share of their customers who do come by car; there are plenty of cases testifying to the attraction, to customers, of places less dominated by cars. Parking on a side street gets you as close to the shops as using a car park gets you to a superstore or shopping mall. Still, it’s a frightening a risky change to make.

Provision of parking on the side roads would also be opposed by some residents, who see parking supply already exhausted. To address this, the Council should reduce parking demand by raising resident parking permit rates in the Green Lanes area, and then rebate the increase to households as a credit on rates – i.e., residents would pay more if they parked, but get the rebate whether they had a car or not. (There may also be a case for separate CPZs East and West of Green Lanes; I’m told that some people from the East side of Green Lanes drive the short distance to the Harringay and Hornsey rail stations and park on the street there before get the train, something we can do without.)

Both sorting the traffic outside of the Arena Shopping Park, and sorting the parking and loading on Green Lanes, would be big steps, and politically difficult. Whoever writes announcements like the Council’s “Active travel to aid social distancing” knows that. That, I expect, is why, despite TfL’s rating of Highest Priority for an emergency bike route on Green Lanes; despite the actions of Enfield to the north and Hackney to the south, which make us the missing link; depsite the growing Green Lanes cycle traffic which occurs despite the congestion and evident danger; despite the pathetically slow buses; despite the geography which makes this such an obvious route both for cycle commuting and for cycling to local shops, services and schools – despite all of this, a Green Lanes cycle route is not mentioned by the Haringey Council at this time.

We should be able to cycle safely, to work or to school or to go shopping. And people riding on buses should not have to sit patiently in traffic so that a few people can park right where they want. This has long been an pressing problem – for reasons of air pollution, diseases of inactivity, carbon footprint and so on. Now, as we emerge from the COVID lockdown, it has become an unavoidable one.

We were back in California for a visit last year. It was the end of a road trip, across the US in June. There were fires in New Mexico and Colorado as we passed through, but it was California that was a shock. We crossed the Sierra Nevada at Mamouth to visit Devil’s Postpile, and immediately we were in smoke an ash from a fire in the John Muir Wilderness a short way away. Helicopters, fighting that fire. We saw the great postpiles…

We were back in California for a visit last year. It was the end of a road trip, across the US in June. There were fires in New Mexico and Colorado as we passed through, but it was California that was a shock. We crossed the Sierra Nevada at Mamouth to visit Devil’s Postpile, and immediately we were in smoke an ash from a fire in the John Muir Wilderness a short way away. Helicopters, fighting that fire. We saw the great postpiles…

Devil’s Postpile: worth seeing

then walked, through smoke and a drizzle of ash, across the scar left by the Rainbow Fire of 1992. There was a forest here before that fire; will there ever be again?

In the midst of that scar, we came to Rainbow Falls, from which the fire got its name. Still worth a visit.

The next day, we crossed Tioga Pass and headed across Yosemite into the Central Valley. From the western boundary of the park, for the rest of our visit – another month – we were in smoke and haze, rarely seeing fire but knowing that there were active fires in every direction.

Much is made of houses and even towns burning, and of the problem of houses built scattered in woods on the urban fringe. Yes, that’s a problem: the fire damage is greater, both because houses burn and because the priority of protecting houses can compromise that of minimizing the spread of the fire; insurance companies, the state legislature & local planning commissions will need to sort it out. But, for the houses amidst the trees, we can miss seeing the bigger picture: we are watching the creation of deserts. These Mediterranean climates, which have always been warm and dry, are now getting drier, and hot. The vegetation, live and dead, which had before been part of a healthy landscape, is now just fuel. Mature deserts don’t burn so much, because there’s not much to burn. These places will keep burning, year after year, until there is nothing left to burn.

Note (1st October 2019): The post below was written in April. Today at the Conservative party conference, Home Secretary Priti Patel smirked while she declaring she will “end the free movement of people forever” as if that were driving a stake through a vampire’s heart. The Labour party, on the other hand, has made some progress, the party conference voting overwhelmingly to support free movement; yet Shadow Home Secretary Diane Abbott makes clear that the leadership doesn’t feel bound by that – so, despite the appearance of progress, my plague-on-both-your-houses must stand.

The original post: It pains me to see the leadership of the UK Labour Party doubling down on its opposition to continued freedom of movement between the UK and the other 27 countries of the EU. A few impressions:

Westminster politicians don’t understand this issue, because they are typically more inward-looking, less international, than their constituents. British political careers famously begin at university and of course continue within the UK, with the MP being somebody who has devoted years to getting the support first of party members and then of voters, almost all of them UK citizens. The upper levels of the civil service are likewise extremely British. Contrast that with work in most sectors of business, education, or the health service, where an international cast of both co-workers and customers/clients/students/patients is the norm, and where careers often include opportunities for work abroad. My guess is that, relative to other Britons of the same age and education, most Westminster politicians, whatever the party, don’t have a clue of the extent to which freedom of movement within Europe has become a part of the lives – and the identity – of many of their constituents.

The university where I teach, a mile and a half from the Palace of Westminster, might as well be on a different planet.